Vestibular paroxysmia (VP) is a rare dizziness syndrome characterized by recurrent, brief episodes of dizziness. The condition is typically caused by a neurovascular compression of the vestibulocochlear nerve[^2], but it can also be secondary to space-occupying processes in the cerebellopontine angle. There are also idiopathic cases without identifiable cause [^1].

Epidemiology

Vestibular paroxysmia is a rare condition. In a specialized dizziness center, it accounts for about 3% of diagnoses. The average age of onset is between 47 and 51 years, with both genders being affected equally. Cases in childhood are very rare but show similar symptoms to those in adults[^1].

Symptoms

The main symptoms of vestibular paroxysmia are frequent, brief attacks of spinning or swaying vertigo with gait or postural instability, lasting from seconds to minutes. The attacks usually occur spontaneously, but can be triggered in some patients by certain head movements or positions. Hyperventilation can also provoke attacks and nystagmus. In extreme cases, up to 70 attacks may occur per day[^3].

Accompanying unilateral auditory symptoms such as tinnitus or hyperacusis may occur, either during the attacks or in the attack-free intervals. Nausea, vomiting, loss of consciousness, or falls are untypical. In rare cases, vestibular paroxysmia can be associated with other symptoms such as a facial hemispasm or trigeminal neuralgia if adjacent cranial nerves are also affected.

Pathophysiology

It is presumed that the dizziness attacks are caused by compression of the vestibular part of the vestibulocochlear nerve, similar to other neurovascular compression syndromes like trigeminal neuralgia or facial hemispasm[^2]. The compression can lead to partial demyelination of the axons, resulting in ephaptic discharges (pathological interaxonal transmissions). These can be triggered by arterial pulsations or sensory input during head movements. The proximal part of the nerve (the root-entry zone), which is surrounded by oligodendrocytes, appears to be particularly susceptible[^1].

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is primarily based on the typical history of short, frequent dizziness attacks. The diagnostic criteria were established by the Bárány Society and distinguish between 'definite vestibular paroxysmia' and 'probable vestibular paroxysmia' [^4].

Imaging

Imaging with high-resolution MRI sequences (e.g., CISS/FIESTA) can demonstrate a neurovascular compression of the vestibulocochlear nerve. However, such contact is also found in a significant proportion of healthy controls (up to 55%) and is thus not proof alone of symptomatic vestibular paroxysmia[^1]. Imaging of the brainstem and inner ear is mandatory to exclude secondary causes.

Treatment

Conservative

Conservative treatment of vestibular paroxysmia essentially involves medication with sodium channel blockers such as carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine[^1].

Surgical

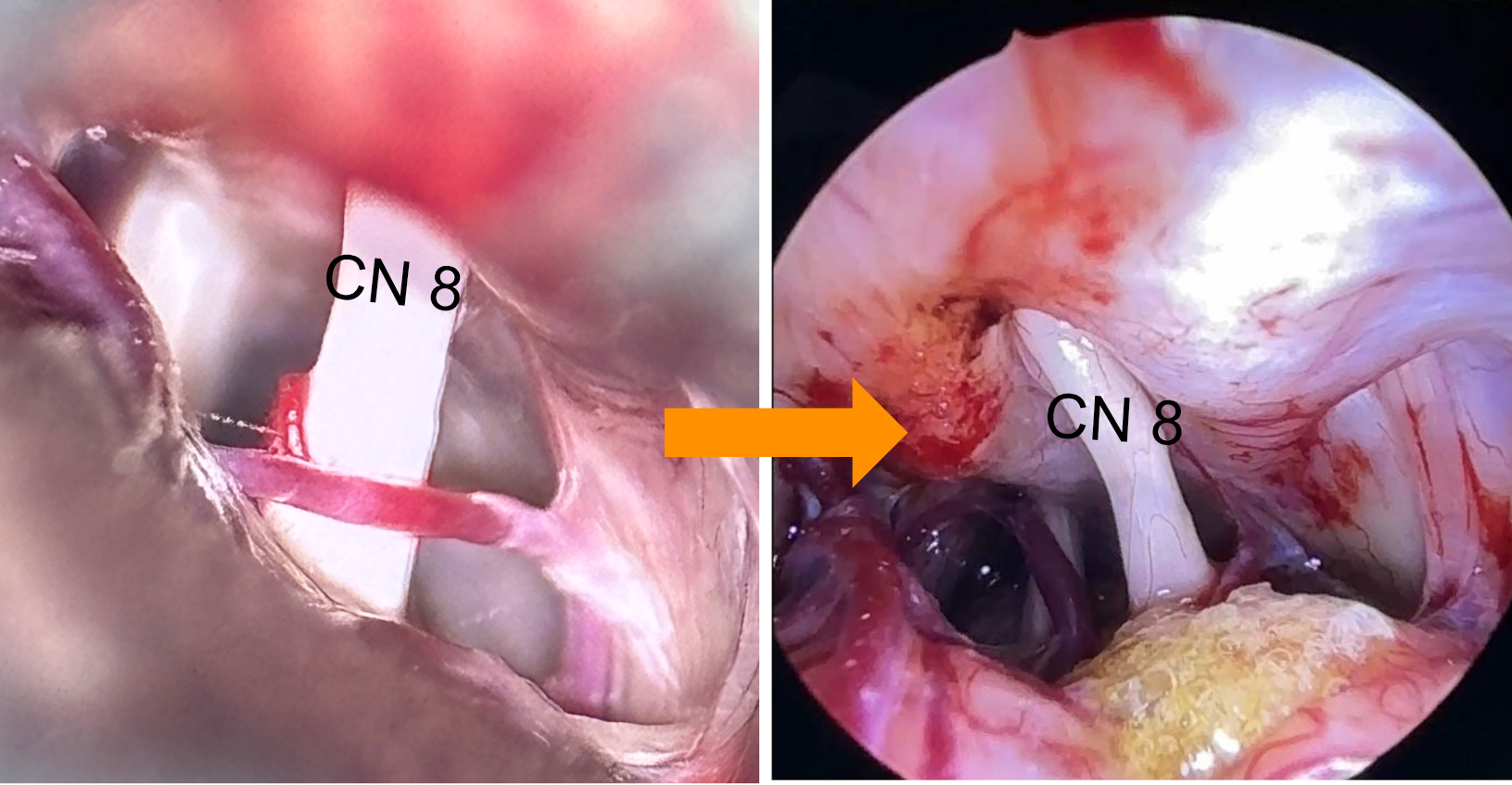

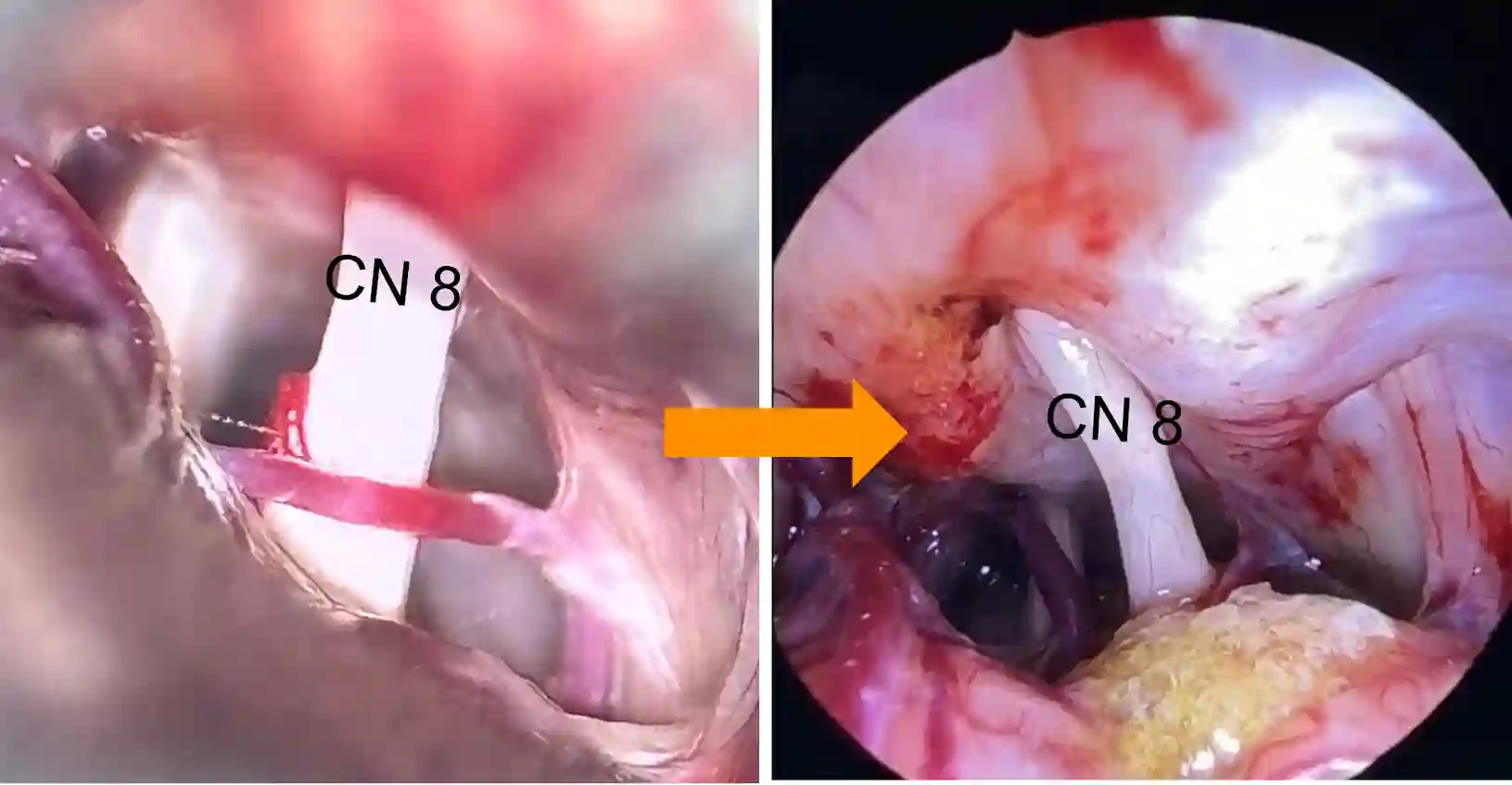

Microsurgical decompression is an option for patients with vestibular paroxysmia who cannot tolerate medication therapy or where it is not sufficiently effective, and where MRI imaging shows a vessel-nerve conflict of the vestibulocochlear nerve.